Jeannie Vanasco has unintentionally built a reputation for an unusual degree of grace and forgiveness than your average human (me). Most notably, her second book, Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was a Girl, is one in which she investigates her rape and interviews her rapist. Over the course of the book, which she wrote in eight months (perhaps no coincidence that she moved through it quickly—can you imagine such an assignment?), she develops a working relationship with this man in search of understanding of what happened.

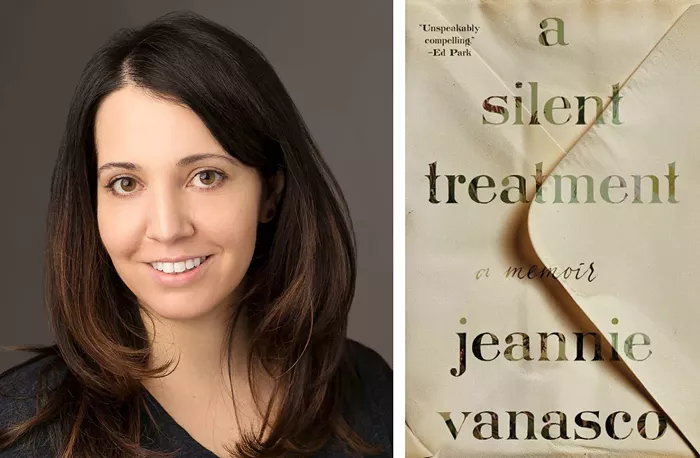

Vanasco’s third book, A Silent Treatment—a memoir about her mother’s chronic silence toward Jeannie while living in the basement apartment of the home she shares with Jeannie and her husband—is, again, an interrogation of her own anger, resentment, and handling of a very different but painful trauma.

When I interviewed Vanasco, she spoke about the core feelings behind the book. “I’m very anxious, and the silent treatment ratchets that way up,” Vanasco said. “I didn’t know what the rules were in the relationship. I wanted to make my mom happy, and I didn’t know how I could always do that. If she was unhappy, I would feel deeply unhappy. A friend recently asked, ‘Have you heard the term codependent?’ I’m like, ‘Yeah, yeah, I know. I know.’” Not sure what she’s being punished for, over and over again, Vanasco is sent into spins of obsessive reflection, seeking a reason, seeking freedom from the seeking, and trying to apply the rules of healing from codependency while utterly unable.

She sought advice via ongoing conversations with her Google mini smart speaker, therapists, colleagues, and dear friends about how to handle her mother’s many months-long silences waiting for her when she got home, active directly under her feet in the very room while she wrote this book. Her relentless search for a solution rings as true and as cyclical as any tumultuous relationship I’ve ever had. “I would read all these psychology studies and these rules about how to deal with someone who uses the silent treatment, especially somebody who inflicts it repeatedly,” Vanasco said. “How you’re not supposed to apologize or try to break it. But [I thought] maybe this advice wasn’t going to work for every person.”

We watch her hide in her car, reluctant to go inside her own home, struggling with every detail of how to approach or not approach. “At the beginning of the book when [my husband] Chris says, ‘Why don’t you just go down there?’” Vanasco said, “I make up all these excuses. From a craft perspective, I think it’s interesting. From a life perspective, it’s awful. But from a craft perspective, my inability to go down there to have a disagreement with her, confront her, that was interesting. Had I been able to do it, the story might have just ended, we’d have a different narrative arc. In storytelling, there’s often a tragic flaw for a character, and that tragic flaw is if they would just do or say this one thing, the whole story would end.”

A Silent Treatment is constructed in fragments surrounded by lots of white space, and an undiscerning reader might assume that this book is a journal, written in real time. That couldn’t be further from the truth, and she breaks that fourth wall over and over again to make it known. “I include the meta elements because it allows me to acknowledge that this is really hard. It wasn’t effortless, even though it may read that way. I want it to read like it unfolded in real time, but it definitely did not.

“It does matter to me a great deal how something reads. I wanted there to be a lyricism that didn’t necessarily come from each sentence on its own, but from how the book moved and how it enacted thinking. I wanted it to read as spontaneous. After I had a coherent draft, I went through and circled the nouns, objects that might come back, so the lyricism didn’t come from the individual sentence, but from the movement. I’m really interested in how to reproduce the mind. The parentheticals that enter almost as intrusive thoughts: I thought the repetition of those [and those particular objects] could provide some cohesiveness, because I would hear her words in different ways when they would repeat.”

Repetitive quotes from her mother and, as Vanasco mentioned, specific objects, do indeed create a movement inside the space of the house and in the book, but also a claustrophobia. The frequent white space allows us, the readers, to breathe. Vanasco is kind this way. I considered the rules she set for herself about repetition in this book because it so colored the structure for the story.

“My rules [for writing this book] kept changing. I figured out that I was going to contain it within a single silence. Of my mom’s silences, I’d count the days, though I wasn’t always quite sure when it started. The longer it went on, I’d lose track of time and just stop counting. I wanted the form and rules to reflect the experience, so the [recurring] parenthetical interrupts allowed me to move around in time. One rule was, how do I break out of time while still having [the story] seemingly unfold in [chronological] time? Some of what [my mother] said breaks out of the parentheticals and becomes an organizing device, because her words would get stuck in my head, and pretty soon they’d be dictating how I see myself.”

While she and her mother share a mailbox, furniture, even a name, we witness Vanasco’s squirming to either make peace with her once and for all, or try to ignore and remain unaffected by her silence.

What makes Vanasco unable to do either seems to be her commitment to giving others grace, and offering herself some understanding, same as she sought in her first two books. In this book, she’s upped the ante because she’s attempting all that from inside the pain, writing as it’s happening. If you have or have had an alcoholic or mentally ill parent, this agony will not be unfamiliar to you. And yet, she paints her mother generously. She tells us again and again of how her mother wants her to write this tale on her own terms. Her mother takes a very Anne Lammot stance: “If I didn’t want it written about me, I shouldn’t have done it.” The agony of mother-daughter love is the diva of this book—an agony that is inevitable and somewhat self-imposed. I’m a reader who simply couldn’t have given the room or grace to my particular mother that Vanasco afforded hers.

It should be clear by now that Vanasco paints herself as much as the antagonist in this memoir as she does her mother. At the same time, the scenario begs the question: How much is too much grace? Or, more accurately, when does grace cross over into doormatting yourself? Where do our responsibilities, our kindnesses, our mutual obligations to each other begin and end? How do we care for each other, and how do we know when we have to stop or destroy ourselves? When it’s costing too much? In her relationship with her mother, Vanasco did eventually find a stopping point.

“I was angry. It was really hard for me to acknowledge that. I feel bad being angry at my mom because she was in pain, circumstances were tough for her, and she was living in the basement. I could see why she was behaving the way she was. So it took me a while to acknowledge, ‘Okay, this is not fair. She can be upset, but she doesn’t have to treat me this way.’”

And yet, she confessed that guilt and shame are inspiration for her. These terrible feelings drive her. “Guilt and shame give me momentum. Each of my books has been for someone, even if it’s not portraying somebody in the best light. But it’s really hard for a book to be for and about someone. If you’re being honest and you’re portraying somebody in all their complexity, you’re including their flaws. I wanted to do this for [my mother]. But I felt guilty. I’m aware that I need to show and acknowledge flaws. Even though my mom says, ‘Nobody’s perfect, you have to include the bad stuff.’”

The way we get no tidy, perfect growth or ending in this book had me wondering what was next for Vanasco. “The next book deals with mental health. It’s under contract with Tin House. It was something that I realized I’d never written about. I’ve written about mental health, of course, but I’d never written about being on social security disability for more than a year. And living through this time, when so many people are losing access to care, losing access to insurance, getting kicked off Medicaid: that’s all very much on my mind. I don’t know what I would have done without it. It was an extremely hard time, being in and out of the hospital. I needed that time away from having to work multiple jobs so that I could find doctors and figure out the medication. I’ve never written about that.”

Jeannie Vanasco’s A Silent Treatment is out Sept. 9 through Tin House.