With his collection of new essays, No Sense in Wishing, culture critic and former The FADER editor Lawrence Burney shows the uninitiated that he’s got chops for days, holding his own among living legends like Hanif Abdurraqib and Kiese Laymon.

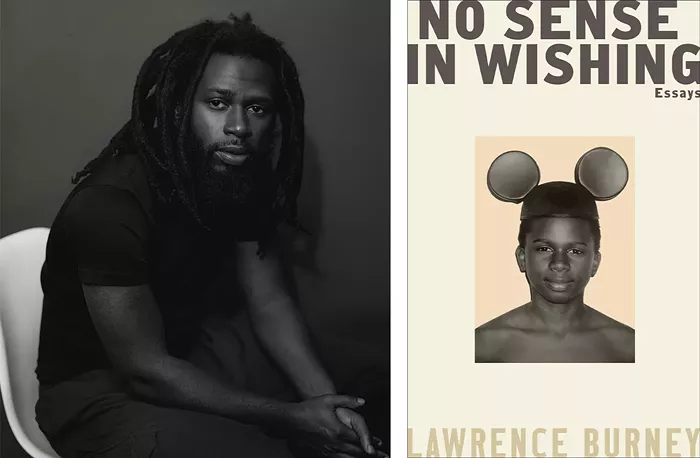

I didn’t know about the DMV (District of Columbia, Maryland, Virginia region) before reading his book. I hadn’t heard of seminal punk band Bad Brains, which is very embarrassing because holy shit, what a band (and because they no doubt influence a favorite local band of mine, Beverly Crusher). And I’d say I have a rudimentary understanding of rap and hip-hop, as ’90s R&B was where I spent my time growing up, and I’ve stayed thirsty for belters and runs ever since. Still, while Burney’s writing is deeply rooted in music I have a distant relationship with, his book gripped me. From the photo of him as a child in Mickey Mouse ears on the cover (taken by his talented artist uncle Derrick Adams) to his completely disarming introduction, to his timing, storytelling, and voice, he immediately made me a devoted fan.

His rhythm, and what reads like natural talent on the page, is built from a decades-long grind up through the ranks. “This isn’t the book I thought I’d write if ever afforded the opportunity to write one,” reads his first sentence. Regardless, the book reads like a necessary culmination of that work, while also suggesting that this writer has much, much more to say. This humility, this honesty, this forthcoming voice with narrative style loaded with tension and questions and possibility: This man can write. It’s exciting to read him, and I’m saying this knowing just 10 percent of the musicians he writes about. But now I’m listening to early Lupe Fiasco and Asake and MIKE. It’s an education in and a touchpoint for writing relatable human experience, regardless of the details, which is exactly what he aimed to create.

“When I was first figuring myself out as a writer, I was mimicking people,” he says. “A lot of the popular writers wrote about things happening on the national scale because that obviously gets a lot of eyes on you. I didn’t understand analytics at the time, but I could tell that it wasn’t a lot of people engaging, so I started to just go out and explore what was happening around me. I had this dual consciousness of being very committed to what’s happening at home [in Baltimore], but also knowing how to filter that in a way that could be palatable and appealing to people outside of home. I’ve always tried to navigate that balance of committing to being a documentarian of my region, but talking about the emotions and the storytelling, things people from anywhere can connect to. That’s the most effective storytelling: when it transcends where it’s based.”

While reading this book, I was overwhelmed by the expertise firing on so many cylinders: Burney has style, his ideas come fast, and the pace of his language is faster. Yet it’s all so smooth; you can read the book solely for sound without realizing you missed the meaning. It’s one to read over and over again. I wondered how much music influenced his writing.

“I don’t think of it as music on a line level,” he tells me. “But I did conceptualize my approach to bookmaking based on the way that I consume music. I absorb music more than I absorb everything else. I obviously watch film, I read books, but music is the thing that I’ve been critiquing for all of my adult life. I thought about the things that make a strong album. I think strong albums are pretty concise. I think they have a strong conceptual throughline. Obviously, it has to be sonically engaging and dynamic, but for me, the thing that I search for in music is the story being told. What am I learning from this person? How effectively is this person bringing me into their world? Do I know much more about this place, and this person, based off of what I just absorbed?”

Then, there are the recs. The critiques. The dozens of musicians, films, books, comedians, neighborhoods, and friends worth looking up.

“I was hoping that, at the end of this book, people would not only have a really strong sense of who I am, but, more importantly, the places that I come from. My favorite thing when I’m absorbing anybody’s creative output is how much referential information is within those contents. If I listen to an album and come away learning about five artists that I never knew about, [or] if I read a book and come away having learned about this place, this album, this historical figure, how XYZ works—those are the things that stimulate me the most. I really was trying to create a pretty intense, stimulating experience for people not only learning about me, but about so many things that contribute to who I am.”

Pretty intense, indeed. I have months’ worth of music, film, books, historical events, and contexts to take in, and when I told him that, he smiled. Mission accomplished.

But of his storytelling, I wanted to hear more. This is a book about Baltimore, and not. It’s a memoir, but also a history of the DMV and of this country. He touches on so many niche yet critically important and influential movements globally, I was looking for how he put it together, especially because he also critiques the “traditional” narrative arc structure and who decided that it is the gold standard for storytelling.

“I definitely think about [narrative structure],” he says. “It all depends on what I’m writing about. A lot of [my style] comes from a journalist background, where you have to be informative. You have to provide materials for people to verify what you’re saying. You have to be descriptive enough so that it’s engaging [to a reader] who has no idea what you’re talking about. I try to smooth that out by not over-explaining. I like dropping people into a personal anecdote or story, and then zooming out and giving the broad strokes. Give some history on it, some contemporary examples, and then zoom back into something personal. The personal things hook people, the information keeps them, and the end falls wherever it might fall. I don’t think I did anything necessarily clever with structure. I think I’m very much still, like, a student of the craft. I wouldn’t say that I’m at a place just yet where I’m being structurally experimental.”

I really, really can’t wait until he is. And even in this answer, Burney gives me more to chew on. Where in this piece have I hooked you? Where have I provided information? Am I riffing? And where will this end?

What I’m saying is, reading No Sense in Wishing was a pleasure. That said, it also takes on the complexities and nuances, joys and celebration, pains and flagrant hideous injustices of Black American life from his illuminating and singular perspective. The last few chapters will take you for a ride through niche, global, and/or familiar arguments— from the racist history of Baltimore steel mills, to Richard Pryor’s fascinating take on using the N-word, to the similarities between Black American and South African mentalities, to the academic studies of Africans’ travel to the Americas long before Columbus. I’m telling you, he riffs. Hard. And like with any skilled artist, it’s his voice and vision that create a relationship between it all. In the writing itself, he finds human likeness, globally. Tell me that doesn’t make you feel good. Tell me you don’t want to know how he does it, and what other specific and fascinating tales he recounts in this book.

The story behind the title, No Sense in Wishing, comes from a moment you’ll have to read about in the book, but it involves a young woman in a tough spot being asked what she would wish for.

“I’ve had many setbacks and hard resets,” says Burney. “I’ve done things I didn’t want to do. I would say that’s the anatomy of the title. It’s not ‘no sense in wishing’ in a cynical sense. At the heart of it, it’s saying that there are things I believe I need [in order] to get me to that next milestone. It’s about mining your environment for things that could be useful to your progression.”

Have you ordered the book from your favorite independent bookstore yet? Do you see how you need this voice in your life? If, like me, you’ve missed his decades of writing about Kanye, Kendrick (and Drake), Tierra Whack, Megan Thee Stallion, dirty policing in Baltimore and beyond; his film reviews, profiles, and cultural reporting and editorial work for Vice, The FADER, the Washington Post, Pitchfork, the Baltimore Banner, and his own media outlet True Laurels: Do not miss this book. Because there’s so much more coming.

“I’m nurturing myself as a storyteller,” he says. “I think I’ve spent probably the past decade of my life more of a journalist, writing for different publications, moving around and connecting with people. All of those experiences are feeding into this next chapter of my journey—bookmaking, filmmaking, telling stories with fewer parameters. On staff, you typically don’t get to write anything longer than 2,500 words, so [to write this book], I had to recalibrate the way that I approach my own work and the permission that I gave myself to ramble, to dig deeper. How can I continue to challenge myself to grow on an artistic level? … There are certain things I wrote about in this book that I felt needed to be resolved within, and writing about them helped me come to terms with emotional hindrances. I hope that my work continues to lead me to those types of revelations. And that in the process, I become more useful and more enlightening and more of a resource to the people around me.”