YouTube places flagrantly pirated videos next to ads for politicians including President Trump, as well as corporate giants like JPMorgan, General Motors and Pizza Hut, according to a bombshell report – and insiders claim Google is turning a blind eye to the shenanigans as it rakes in billions in ad dollars.

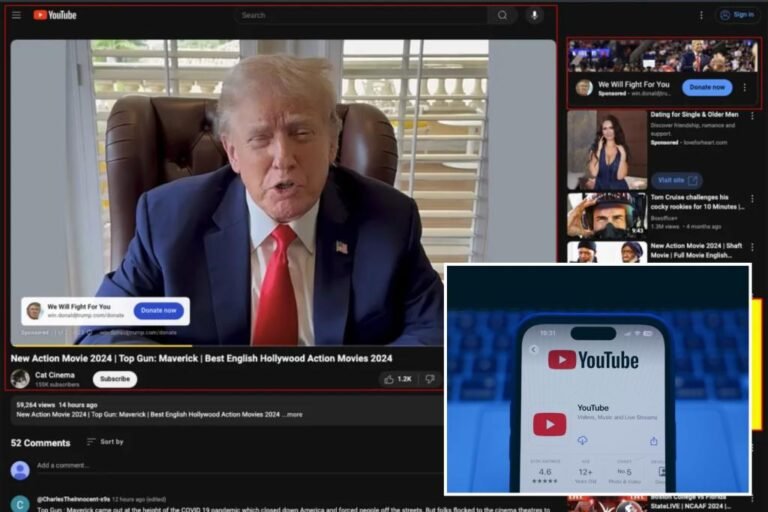

Last September, YouTube ran a Trump National Committee ad before what looked like a pirated version of the Tom Cruise blockbuster “Top Gun: Maverick.”

Last month, an ad for Procter & Gamble’s Olay body wash ran alongside an apparently pirated Russian-language version of Netflix’s “Squid Game,” according to the report.

Elsewhere, ads for Pizza Hut and General Motors ran alongside a pirated Spanish-language version of the 2025 movie “Sinners,” according to screenshots included in a 300-page report compiled by Adalytics, a research firm that partners with Fortune 500 companies.

The latter were later removed to a copyright request by Warner Bros, and the other two were eventually taken down over copyright claims.

Nevertheless, YouTube scarcely ever gives refunds to brands after it removes videos that violate its own policies, media buyers and advertising executives told The Post.

“They’re letting it happen,” said Erich Garcia, a longtime marketing executive. “It’s because they are financially benefiting from this. They are pocketing the money and continuing on.”

Garcia said he raised the issue directly with YouTube in early 2023 after noticing bizarre trends while serving as head of paid media at Quote.com.

“I would see these really random YouTube channels, typically foreign language with very small viewership, all of a sudden — in the course of like 20 minutes — rack up thousands of dollars of spend,” Garcia said.

These weren’t isolated, one-off incidents. Garcia said as much as 50% of Quote’s ad spending during a given period would show up in YouTube’s reports marked “Total: other” — indicating that the channels where the ads had run had been removed while failing to identify them.

Eventually, Garcia gave a presentation to YouTube staffers, a copy of which was viewed by The Post, which showed that nearly $300,000 — or more than 40% — of Quote’s spending, was unaccounted for in YouTube’s reports.

He said Google representatives later provided him with a $50,000 account credit, though they didn’t admit it was because of the issues he’d flagged.

Meanwhile, Adalytics captured video in which Trump campaign ads ran alongside multiple pirated broadcasts of college football games, including a matchup between the Colorado Buffaloes and the Colorado State Rams last fall.

That video was later removed after the account was “terminated,” according to YouTube.

A YouTube spokesperson said the Trump campaign ads flagged in the Adalytics report ran on videos that were correctly identified by YouTube’s “Content ID,” a safety tool that scans for copyright-related infractions, and removed from the platform. The channels responsible for the violations were banned.

“When we become aware of channels that repeatedly upload content they don’t own, we terminate the channel, and if ads were running on this content, we credit the advertiser,” a YouTube spokesperson said in a statement.

Content ID flagged more than 2.2 billion videos in 2024 alone, the company said. In more than 90% of cases, rightsholders opted to keep their content on YouTube in exchange for receiving ad revenue.

When possible, YouTube provides credits to advertisers whose ads ran on channels that violated its policies, the company said.

The White House declined to comment. The Republican National Committee did not return a request for comment.

Kamala Harris’s campaign encountered similar issues, as did major corporate brands like NBCUniversal, US Bank, T-Mobile and many others, according to Adalytics.

Advertisers have been up in arms about ads running against illicit YouTube videos for at least a decade. In 2015, ads for big corporate brands like Toyota and Anheuser-Busch ran alongside videos of ISIS beheadings.

In 2017, Lyft pulled advertisers off YouTube after its commercials ran on a white supremacist group’s channel.

Every morning, the NY POSTcast offers a deep dive into the headlines with the Post’s signature mix of politics, business, pop culture, true crime and everything in between. Subscribe here!

That hasn’t stopped YouTube from becoming a cash cow for parent company Google. The platform raked in a whopping $36.1 billion in revenue from digital ads in 2024 – including its first-ever $10 billion quarter in the last three months of the year.

While YouTube sends placement reports about their ad campaigns, sources say the reports are vague and difficult to parse. Some campaigns can have thousands or even millions of entries logged in a spreadsheet, making performance analysis nearly impossible for smaller businesses.

“They have controls in place, but it appears that they don’t work as well as they say they do,” said one ad executive who asked not to be named. “It is a very complicated ecosystem that they’ve set up. And it can make it seem as though an advertiser, large or small, is buying in an open exchange where you can end up on channels or videos with unsafe, inflammatory, or foreign-owned content.”

The industry veterans said YouTube videos that get taken down show up in Google reports in a category titled “total: other.” The reports give no details on when or why the videos were removed, leaving advertisers at a loss to explain how their money was spent.

One media buyer said it was “utterly impossible” to get a full understanding of how and where brand ads were running on YouTube.

“You can’t know for certain what was what,” the buyer said. “You can’t get much transparency into things that were removed.”

To vet YouTube’s refund policy, a second media buyer performed a test in which ads were specifically marked to run in channels that the buyer knew had been running pirated videos. YouTube removed the videos, but didn’t give a refund, according to a copy of a YouTube report viewed by The Post.

“Why are they not giving a refund for that? If it was not good enough for their policies, but it’s good enough for you to take the advertiser’s money?” the second media buyer said. “it seems like they’re really focused on the monetization aspect and not so much on the success of campaigns for advertisers.”

YouTube pushed back on assertions that its placement reports are too vague and said it encourages advertisers to contact their account managers if they have questions about receiving “make good” credits.

Earlier this year, a US federal judge ruled that Google operates two illegal monopolies related to digital advertising. The Justice Department is pushing for a breakup of the company to restore competition.

Critics have argued that a lack of competition has allowed Google to skate by without meaningful product and safety improvements.

For now, Garcia said advertisers have little choice but to eat their losses and continue working with YouTube due to its massive audience.

“It’s like ‘kiss the ring,’” Garcia said. “Where are you gonna go? There is no competition to YouTube.”