Log on to Facebook for 10 seconds and you’ll agree: It’s a good time for people to pick up an actual book. Which may explain why Mam’s Books, a small Asian American bookstore in the center of Chinatown, feels less like retail and more like a revolution. That it presents like a neighborhood living room is by design, the kind with family photos atop shelves, a couch that’s seen better days, and smiling elders eating noodles in front of the window. Each piece of the shop a little story of its own.

By the time Sokha Danh wrestles the rolling gate open and pops the heavy locks, the neighborhood’s already moving. Buses sigh at the curb, cleavers thump somewhere down the block. He drags the Mam’s Books sandwich board to the sidewalk to signal the start of a new day, door propped open behind him, letting in sunlight and scents from nearby shops. Some mornings there’s music: Blue Scholars, J. Cole. Sometimes Wong Fu vids. Other days, just silence. He’ll tell you he’s setting the pace, establishing certainties in an uncertain world, but his passion for building consistent community ignited long before Mam’s opened, back when the White Center Library gave him and his siblings a seat, a stack of books, and a space no one hurried them out of.

In many ways, he’s been trying to return the favor ever since.

The First Page

In the ’80s and ’90s, White Center was not known for much good. But for Sokha’s family, it was where their story began. His parents, both refugees from Cambodia, brought their four daughters (Linda, Vesna, Sopha, and Vira) and three sons (Vana, Ratcha, and Sokha, the youngest) to Seattle to begin a new life.

For two parents with not enough money, and possibly too many kids for what they did have, community resources were a godsend. Like the White Center Food Bank, which helped Kim, the mother, keep the troops fed, and the White Center Library, which helped Mam, the father, keep his children curious, educated, and safe.

Almost daily, Kim and Mam would drop off their clan at the library, sometimes for hours, while the pair looked for work and opportunities. Sokha and his siblings would fan out through the aisles, on the hunt for something that would transport them: Magic Tree House books, Garfield comics, thick cookbooks with glossy photos. The librarians understood the assignment. They knew each of the Danh children by name and saved books for them, and when Sokha needed to call home for a pickup, they slid the phone across the desk like it was nothing.

That mix of access, freedom, and trust that libraries provide their communities is the blueprint for the bookstore. It’s why Sokha never flinches when people spend hours reading without buying, or when an event takes over the shop without ringing the register. The shelves are for anyone to peruse, the chairs are for anyone who needs to sit, and the front desk—if he had one—would be just as quick to slide over a phone.

Good Looking Out

On weekday mornings, it’s not unusual to find two grandmas holding court on Mam’s orange couch, grocery bags at their feet, gossiping in Cantonese between bouts of laughter. Sokha is in no hurry for them to leave—their presence is part of the point.

Almost a decade before opening Mam’s, Sokha worked for SCIDpda (Seattle Chinatown International District Preservation and Development Authority), heading up a Block Watch that facilitated escorting groups of elders on evening walks so they could feel more comfortable leaving their apartments after dark. It was a crash course on the quiet math people do about whether it’s safe to step outside: calculating who’s around, who’s watching, and whether anyone would notice if they didn’t make it home. “They all wanted to walk outside safely, like we all do,” he told me later. “Walking together made them feel seen.” In a time where Chinatowns vanish by neglect as much as by politics, that visibility is its own armor.

But in Sokha’s mind, visibility and safety must go beyond Mam’s. “If the bookstore is the best thing I’ve ever done for the community, I’ve failed,” he tells me. This style of “major-league activism,” as he calls it, has to spill into the rest of Chinatown and beyond: into the shops, the sidewalks, the tiny apartments above.

That’s what he learned from the late Donnie Chin, the Chinatown International District’s unofficial first responder who spent decades patrolling the streets on his own terms. From Jamie Lee, his boss at SCIDpda, he learned how to turn that watchfulness into organizing power. From Ron Chew, another waymaker in the CID, he learned how to preserve it in story and history. All of it shaped his idea of belonging: feeling both safe enough to step outside, and welcome enough to stay.

The Calling

Major-league activism, though, can take its toll. By the time Sokha opened Mam’s, he had carried years of Chinatown community work on his shoulders. It was good work, but also the kind that leaks into your bones. Eventually, it all came to a head—every crisis blurred into his identity until there was no room for anything else. The burnout had been building for months. He journaled nightly, asking higher powers to give him a sign.

Then, one late summer evening in 2020, Sokha was driving down Alki Beach when his calling came to him: an Asian American bookstore serving Chinatown and its community. A way to continue to be a positive force in the neighborhood—the one that showed him the power of participating in society—without sacrificing so much of his well-being to do so.

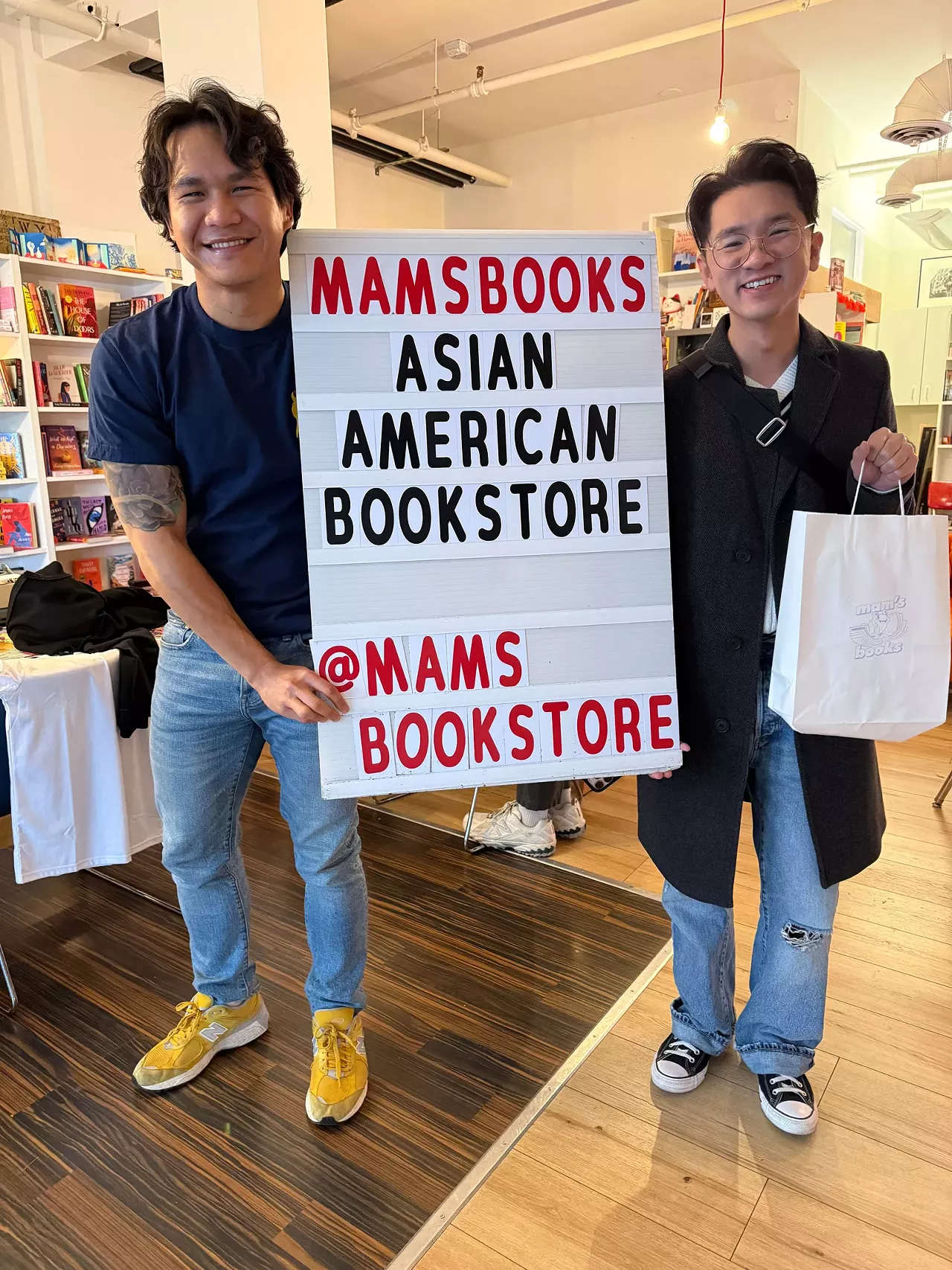

In September 2023, Mam’s Books opened, ushering in a new era in Chinatown. On the last Sunday of the month, the Chinatown Book Club packs the store. The next day, the same couch is a stage for the Orange Couch Open Mic. In between, the store hosts touring Asian authors of all calibers. Each activation brings more new faces to Mam’s, and more importantly, more new faces to Chinatown.

The Heart of Chinatown

When you visit Mam’s, you’ll feel you’re at the center of something important. That’s especially true when you look at a map, which shows that the store lives at the literal center of the neighborhood. Its heart. For Sokha, that centrality goes beyond geography. It’s the reminder that belonging radiates outward, and that a single room, if tended to, can ripple through an entire community.

It brings to mind a Chinese parable his dad used to tell about a toad who knows only the world from the bottom of a well until a passing bird shows him the sky beyond. The toad is now the store’s logo—a reminder not only to look up and climb out, but also to bring others with you. “This bookstore really is a mosaic of everyone who has loved me.”